Deep Learning in Sports and Autonomous Vehicles

October 27, 2023

12 mins read

Deep Learning stack

I am constantly asked about the role Deep Learning plays in sports performance tracking and analysis, so the idea for this post arose. The article explores detail and highlights similarities with perhaps better-known fields of application that may initially appear unrelated, but upon in-depth exploration, prove to share striking similarities in terms of requirements, Deep Learning models and approaches applied as well as engineering techniques. Specifically, the autonomous vehicles tech stack appears to be very comparable to Sports tech in many regards. Here we will discuss each step of a typical workflow: data collection as a form of the world perception, planning and simulation as the data processing phase and, finally, control.

Sports applications

The application of various machine learning algorithms has significantly transformed both real-world sports and eSports along with related industries. These applications cover a range of functions, falling into several distinct but inter-related categories::

- Real-time or Post-Match data collection. This includes data collection of athletes’ performance metrics such as speed, acceleration, and biomechanical data for injury prevention and individualized training plan adjustments. Previously, these data sets were gathered manually, but machine learning has made this process not only more cost-effective and accessible but also enabled the acquisition of data that was previously challenging or impossible during actual gameplay. For instance, while analyzing biomechanical motion requires motion capture systems, which is not a very unscalable approach, deep learning-based computer vision systems now allow data collection during live games. This data is not only utilized for training and game analysis but also proves vital for scouting and recruitment, which was one of the prime areas of data-driven decisions even before the present era of machine learning dominance. Data collection is a valuable resource that can be employed by sports leagues to support referees and facilitate comprehensive game analysis on a larger scale. This information can further be utilized to refine rules, ensure fair play and game balance, and steer the development of the sport as a whole. Additionally, these algorithms are utilized for less apparent applications like anti-cheat systems to detect match-fixing or eSports cheating.

- Machine learning algorithms process collected data to provide tactical analysis to teams by identifying specific patterns in player movements, team strategies, anomalies, and more.

- Outcome prediction: Real-time data processing enables the forecasting of future outcomes, thus assisting in-game decision-making and allowing for swift strategic adjustments during gameplay. The technology’s utility extends beyond sports performance tracking, as it can be employed by betting companies. These companies can use real-time data processing to predict not only overall event outcomes but also short-term predictions (such as expecting a point scoring for Team A in the current situation), efficiently, providing probabilistic negative-latency data streams.

- A robust model for outcome prediction unlocks endless possibilities for simulating diverse scenarios. It empowers teams to test innovative tactical maneuvers and strategies without the inherent risks of experimentation during live games, even automating the search for improved approaches. It’s akin to having a virtual training ground where ideas can be automatically tested with realistic feedback, much like aviation simulations that simulate in-flight failures to refine and enhance safety measures.

- The data collected can be further utilized by ML algorithms to optimize equipment designs and configurations for specific sports, like enhancing the aerodynamics of a bike helmet or designing more efficient tennis rackets.

- Audience engagement. The sports industry can be viewed as an entertainment provider, and machine learning applications have opened up numerous possibilities for fan engagement. These range from automatically adding in-game statistics into broadcasts to automating camera controls for a more engaging events video coverage experience. Additionally, Deep Learning has facilitated the generation of immersive, realistic mixed-reality content to enhance fan involvement and engagement.

Sensor Calibration

Most ML-based workflows heavily rely on indirectly measured parameters, such as an athlete’s speed in sports analysis or the trajectory of a pedestrian for accurate location of other cars in autonomous vehicles applications. Just as in any photogrammetry system, precise calibration is crucial. In practice, this not only involves calibration of a single sensor type or intrinsic calibration alone, but also encompasses extrinsic calibration to align data from different sensors (e.g., cameras, LIDARs, and radars) into a unified space. For example, Trackman 4 Launch Monitor uses radars and a camera for collecting golf club and ball data, or Sportlight system utilizes multicamera and LIDAR data for football players tracking.

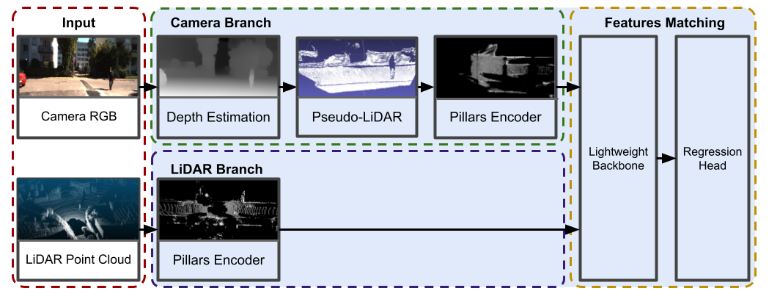

There are various ways to perform calibration, with two major groups: the classical manual calibration process or Deep Learning-based approaches. For example, in deep learning calibration of a multi-sensor setup, a common approach is to bring the data into a common representation. Then, perform feature-matching calibration parameter optimization to align data acquired from different modalities or from different sensors.

Fig. 1. PseudoCal: a Deep Leaning approach to perform LIDAR-camera calibration [1].

Fig. 1. PseudoCal: a Deep Leaning approach to perform LIDAR-camera calibration [1].

It is worth noting there are some algorithms available, which do not require direct calibration. An instance of this is self-supervised depth estimation task can be viewed as such example. However, in this scenario, the “calibration” occurs as an internal process during the model’s training phase.

In addition to the importance of calibrating sensors, optimizing data acquisition parameters by the sensors, such as camera exposure parameters (exposure time, gain, white balance, aperture, etc.), is crucial. This is particularly relevant in situations without controlled lighting conditions: outdoor environments (stadiums or roads). Setting the correct parameters represents a classic example of a dynamic feedback system that can be controlled with classical controllers, like PID or specific algorithms developed for this particular task. Also, it can be managed by a deep learning model. This model can optimize image capturing parameters for the best perception by downstream models, such as generating optimal features for a SLAM pipeline [2].

Perception

Once the sensors are calibrated and configured, it is the time to collect the real world data. The tasks can include objects detection and tracking (players, cars, pedestrian, sports equipment), semantic segmentation to find the drivable area or parts of the playground, direct depth perception, pose estimation for biomechanical analysis and intention recognition.

In many instances, the perception tasks in both sports applications and autonomous vehicles are inter-related. For example, the knowledge of a ball’s position can make it easier to spot pass events, or the state of a traffic light can help analyze cars’ trajectories. This shared nature makes multi-task learning an attractive option for achieving synergistic effects. Another common feature in both scenarios is that they are dynamic, so the temporal domain is as important as spatial. This results in many specialized neural networks benefiting from temporal information. For example, a ball can be detected more accurately and with reduced rates of false positive detections if the neural network has access to information from previous frames [3]. Many neural networks in both domains are also temporal-based by nature due to their tasks, such as temporal event localization or object tracking. Therefore, spatio-temporal multi-task neural networks play an important role in video understanding [3].

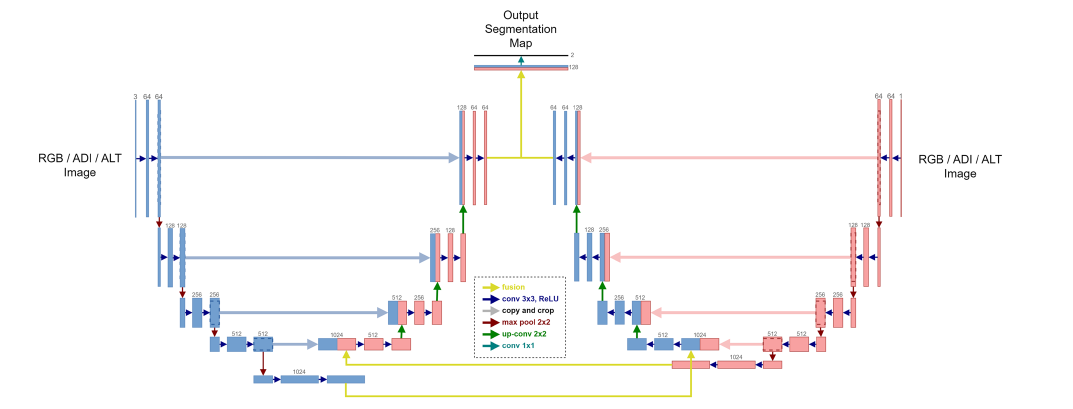

As it was mentioned above, one of the features of real-world systems is that the information usually comes from various sensor types, such as cameras, LIDARs and radars, as well as from auxiliary sensors, such as GNSS receivers, accelerometers, etc. Speaking from the neural networks architecture perspective, in many cases the diverse data can be homogenized in common representation space before (early-fusion) or during (cross- and late-fusion) processing by neural networks [4].

Fig. 2. An example of U-Net style neural network architecture, which was applied to camera and LIDAR data for road segmentation. ALT and ADI are forms of interpolated LIDAR data [4].

Fig. 2. An example of U-Net style neural network architecture, which was applied to camera and LIDAR data for road segmentation. ALT and ADI are forms of interpolated LIDAR data [4].

The main difference between sports applications and autonomous vehicles lies in the absence of ego-motion in many sports cases. Nevertheless, there are typically numerous exceptions. For example, it is quite common to have video from sports TV broadcasts with moving and zooming cameras, which means more degrees of freedom than typical autonomous vehicle setups with fixed focal length lenses, which makes extrinsic parameters online evaluation even harder to master. Additionally, certain sports like racing, skiing, and similar require the use of moving cameras. It is important for algorithms to be adaptable to moving camera conditions or at least have some monitoring in place to detect sudden moves under external forces even for systems where sensors are expected to be stationary. In sports, the seemingly rigid stadium construction can appear very wobbly when there are thousands of excited fans and the sensors can literally sway and wave with the audience!

Analysis, Planning and Simulation

The next stage heavily depends on the actual application of the data. Here are a few application examples for scene analysis and data processing.

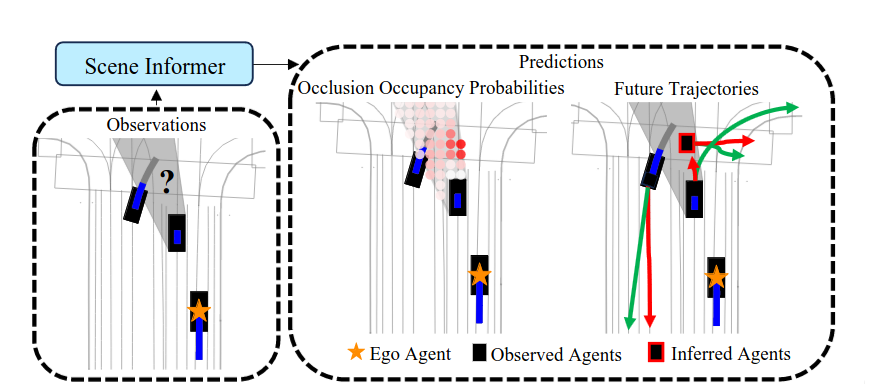

In team sports, many applications are centered around the analysis of player trajectories, for example, to analyze and predict pitch control in football. A comparable task in the world of autonomous driving involves probabilistic trajectory prediction to establish the road occupation map, essential for planning safe maneuvers. Moreover, a common scenario in both fields involves action prediction for subjects beyond the sensors’ coverage. For instance, predicting the trajectory of occluded pedestrians or players beyond the sensor’s field of view is a common challenge faced in both sports and autonomous driving applications.

Fig. 3. Multiagent off-screen players trajectory prediction in football beyond broadcast video coverage [5].

Fig. 3. Multiagent off-screen players trajectory prediction in football beyond broadcast video coverage [5].

Fig. 4. Scene Informer, an end-to-end prediction framework that considers both observed and occluded agents in partially observable environment. It forecasts multi-modal futures for observed agents and estimates occupancy probabilities and trajectories originating from the occlusion for self-driving car application [6].

Fig. 4. Scene Informer, an end-to-end prediction framework that considers both observed and occluded agents in partially observable environment. It forecasts multi-modal futures for observed agents and estimates occupancy probabilities and trajectories originating from the occlusion for self-driving car application [6].

The ‘what if’ analysis, often termed as simulation or scenario planning, is another common ground between these domains. In sports, teams leverage simulation to strategize and understand the potential outcomes of different plays or formations. For example, in soccer, analysts use Deep Learning models to simulate various offensive and defensive strategies to understand how they might influence the game’s outcome. Similarly, in autonomous vehicles domain, simulation is used for testing the behavior of self-driving systems in diverse scenarios without real-world risks and to dramatically reduce costs of real-world data collection for testing scenarios. For example, GAIA-1 model by Wayve creates simulated video environments, which can be conditioned by input video frames, text and action inputs modalities.

Control

One might say that control is an area largely absent from the Sports tech stack. Yet, this perspective is only partially accurate. In the field of autonomous vehicles, cars are directed to follow to a planned course using something like a classical controller (PID could be the simplest example), MPC algorithm or a form of ML agent (an area showing promise in RL application [7]). However, it can be argued that algorithms employing data gathered automatically effectively contribute to the “control” of games. An illustrative instance is the the Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP)’s mandate for Electronic Line Calling (ELC) from 2025 this technology has already significantly impacted the precision and fairness of judgment in tennis matches.

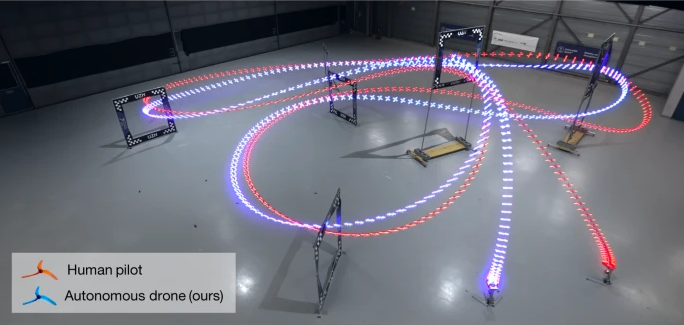

Indeed, beyond these seemingly disparate examples, control also serves as a unifying component between sports and autonomous vehicles. Recently, autonomous drones demonstrated performance levels on par with or even superior to human world champion pilots [8]. Of course, there were a lot of remarkable examples of ML-based agents beating humans in many eSports and board games, but this is, perhaps, one of the pivotal points when ML algorithms can perform better in a sport involving the control of real-world objects. In that regard, there are a lot of developments in the direction of autonomous vehicles racing, for example, The Indy Autonomous Challenge blazing the trail for both: fully autonomous vehicles circuit racing and better ADAS systems for road cars. Essentially, it marks the inception of new nature in sports, where teams are competing not directly on the raceways, but rather behind screens, refining and perfecting Deep Learning algorithms to gain a competitive edge!

Fig. 5. An RL-controlled autonomous drone can compete at the level of human world champions. This was achieved partly because the RL agent was able to select a more optimal path, utilizing the drone’s capabilities more effectively than human pilots. [8].

Fig. 5. An RL-controlled autonomous drone can compete at the level of human world champions. This was achieved partly because the RL agent was able to select a more optimal path, utilizing the drone’s capabilities more effectively than human pilots. [8].

References:

[1]: Mathieu Cocheteux, Julien Moreau and Franck Davoine. PseudoCal: Towards Initialisation-Free Deep Learning-Based Camera-LiDAR Self-Calibration. arXiv:2309.09855.

[2]: Justin Tomasi et al. Learned Camera Gain and Exposure Control for Improved Visual Feature Detection and Matching. arXiv:2102.04341.

[3]: Roman Voeikov, Nikolay Falaleev and Ruslan Baikulov. TTNet: Real-time temporal and spatial video analysis of table tennis, CVPRw2020. arXiv:2004.09927.

[4]: Arda Taha Candan and Habil Kalkan. U-Net-based RGB and LiDAR image fusion for road segmentation. Signal, Image and Video Processing, 17, PP. 2837–2843, 2023.

[5]: Shayegan Omidshafiei et al. Multiagent off‑screen behavior prediction in football. Scientific Reports, 12, 8638 (2022).

[6]: Bernard Lange, Jiachen Li and Mykel J. Kochenderfer. Scene Informer: Anchor-based Occlusion Inference and Trajectory Prediction in Partially Observable Environments. arXiv:2309.13893.

[7]: Fei Ye et al. A Survey of Deep Reinforcement Learning Algorithms for Motion Planning and Control of Autonomous Vehicles. arXiv:2105.14218.

[8]: Ella Kaufmann et al. Champion-level drone racing using deep reinforcement learning. Nature 620, 982–987 (2023).

Note: The title gif was generated from a video of [8].